American Behavior

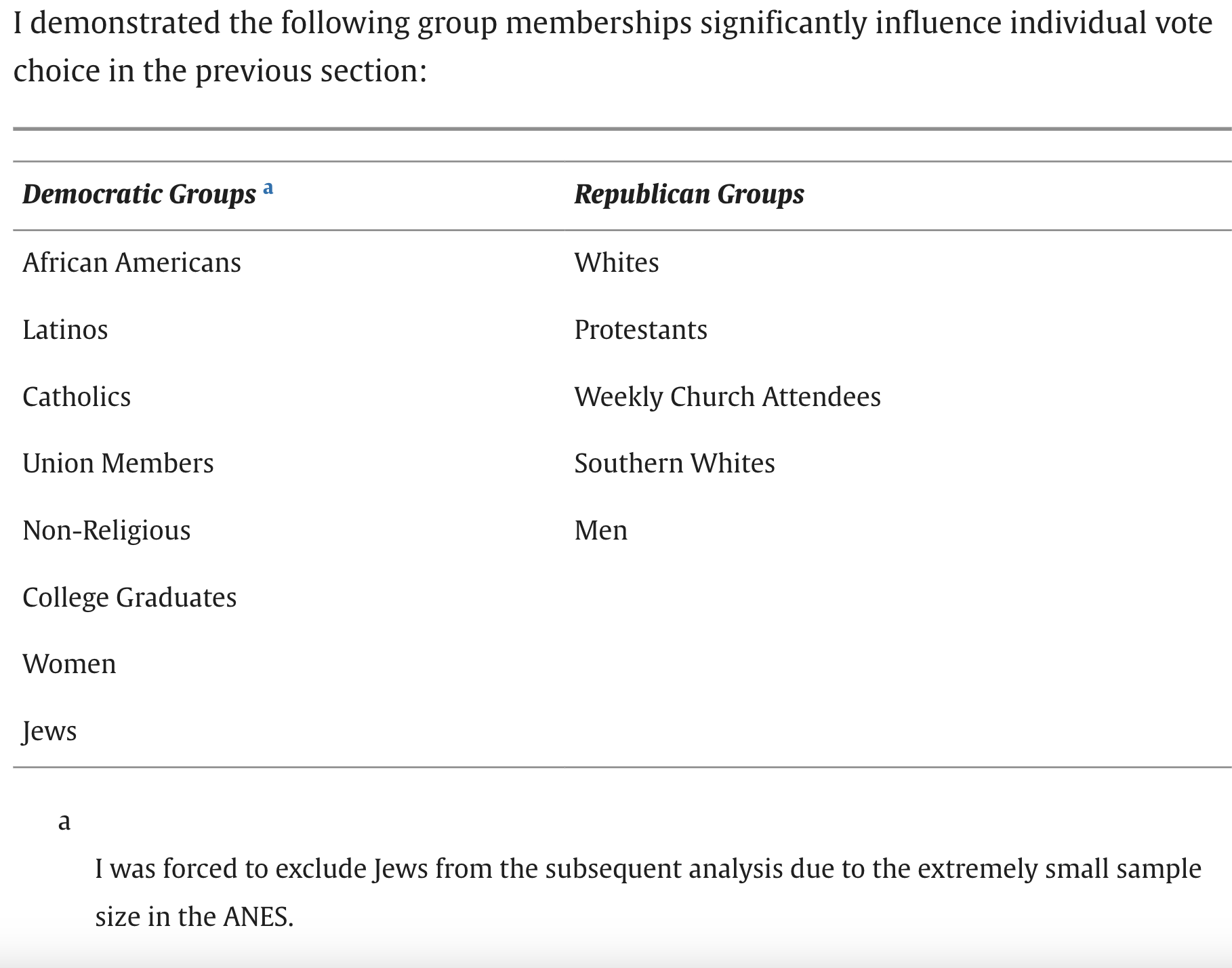

Week 1

Lecture Notes:

- write a reaction paper (300 words)

Essentials of Argument

Argument structure should guide response essays.

we are trying to convince readers we are competent and should be trusted.

starting with a problem and proposing a solution

always be thinking about audience.

just think about the parts of an argument when writing.

Five questions of argument:

what are you claiming?

what reasons do you have for believing your claim?

what evidence do you base those reasons on?

what principle connect?

TK.

design of an experiment is a warrant.

You can make concessions to dissenters

- “admittedly”, “some have claimed”.

Keep it simple, stupid “KISS”

Good warrants:

do readers know the warrant already?

will all readers think it is true?

Craft of Research (select portions)

Important to know your readers

know how political scientists write/read.

You have to know your readers to be able to write to them.

Motivation behind idea and potentially what data would be good for the project and what I would use.

- this is for the research design.

Making Good Arguments

There are claims and main claims

claims = any sentence that asserts something that may be true or false and so needs support.

main claim = the sentence (or more) that your whole report supports (aka thesis).

reason = a sentence that supporting a claim, main or not.

Evidence

something you and your readers can see, touch, taste, smell, or hear; accepted by everyone - a fact.

Where could I go to see your evidence?

Core of a research argument:

- Claim because of Reason based on Evidence

We dont accept a claim just because you back it up with your reasonsand your evidence

as a result, readers may question any part of your argument

Need to imagine readers objections!

Need to justify the connection between the reason and the claim.

this is the WARRANT!

- if you think readers won’t immedaitely see how a reason is relevant to your claim, then you justify the connection with a warrant, usually before you make it.

The five elements:

Claim

Reason

Warrant

Evidence

Acknowledgement and Response

Claim

vague claims lead to vague arguments

Write down your claim. Articulate it. Make it explicit. You can fix it later.

If the reverse of a claim seems self-evidently false, then most readers are unlikely to consider the original worth an argument.

If your claim is true…Why should I care?

arguments are more credible when you address its limitations.

every claim is subject to countless conditions.

- only address ones you expect readers to bring up.

Use hedges for claims.

- gives argument nuance.

Reasons and Evidence

Reasons outline the logic of your argument.

main claim > reason > subreason > evidence

we don’t base evidence on reasons

- we base reasons off of evidence

evidence is what readers accept as fact.

evidence or reports of evidence

- different things.

careful hedging your evidence

Need to explain evidence

Acknowledgements and Responses

The core of your argument is a claim backed by a reason based on evidence.

But you can’t only base your argument off your claims!

You need to anticipate questions readers may ask and respond accordingly.

be self-critical

Steps:

First, question your problem.

Second, question your support

focus first on evidence

Finally, readers may question the connection between your claim and reasons. Your reasons may be irrelevant of the claim.

Think of counterexamples

acknowledge them and explain why don’t consider them damaging to your argument.

can’t acknowledge everything. But can’t ignore everything.

Readers have to accept your definitions!

Goal: THICKEN your argument.

be careful with the word choice when you engage with acknowledgements

Warrants

The logical relevance of your response to your claims.

Readers can still accept your claim as true BUT they may not accept your claim if they think your reasons are irrelevant to it.

we offer warrants to connect a reason and a claim

Warrants are kind of like glue between reason and claim. They tell the reader why they should believe the reason/evidence should be used to support the claim.

Week 2: The Classics

Lecture Notes:

Question for Anand: why did you only assign those chapters of Downs? Isn’t the punchline of Downs that rational voters lead to median voter theorem and the parties being similar to appeal?

Lazarsfeld et al. is considered the Columbia school.

sociological school - Columbia

Rat choice - Downs

social-psychological

Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: Wiley. Chapters 1-2.*

Lecture Notes:

Question: voter competence?

Social-psychological model

- is there really a fight between social group importance with the Columbia school?

About voter decision making.

Michigan model - focused on mass public.

ANES data

Think Columbia school doesn’t have enough a priori hypothesis.

I need to read Zuckerman.

Design: Survey Based

kind of taking individuals out of context.

we need to move beyond community and think about psychological things.

The funnel of causality.

a way of trying to grapple with inputs.

political socialization is going on in the background

Theory: party identification is what comes out of this.

I personally do not see a massive difference between this and the Columbia.

Attitudinal model - Michigan - social/psych - party id model.

party id is an enduring psychological attachment!

Chapter 1: Setting

The activity of voting is as a means of reaching collective decisions from individual choices.

The voting behavior of a mass electorate can be seen within the context of a larger political system.

The empirical materials of our own work lie within a particular historical setting.

this research lies within a sequence of studies on voting.

The study of voting is also concerned with a fundamental process of political decision.

The political system can be idealized as a collection of processes for the taking of decisions.

will focus on just america and only the presidential election.

Contribution (as they outline):

first is the political impact of identification with social class.

second is the psychological determinants of voting preference.

Hypothesis: the partisan choice the individual voter makes depends in an immediate sense on the strength and direction of the elements comprising a field of psychological forces, where these elements are interpreted as attitudes toward the perceived objects of national politics.

data is over 3 presidential elections - 1948 - 1956.

Chapter 2:

Understanding versus prediction

- “we are concerned with prediction per se only as it serves to test our understanding of the sequence of events leading to the dependent behavior.”

There is a social and attitudinal model.

they use attitudinal model.

party identification is vital and acts as a filter.

everything else is secondary.

The use of political attitudes to predict voting behavior hinges upon this proximal mode of explanation.

Social model is more concerned with membership in social groups and their impact.

Doesn’t: social group -> party id -> vote decision?

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper. Chapters 1; 3.*

Lecture Notes:

Rational Choice approach.

Formal model.

Question: Why do people vote?

Question: How do people make decisions?

Questions: How do parties position themselves to win reelection? - we don’t really discuss this.

I need to read liberalism v. populism by Riker.

Goal-oriented actors.

we are thinking about Downs in terms of his assumptions

- the basic idea of rationality.

Anand doesn’t include the chapters on the interest groups/political parties.

Downs is filling out the scope of his argument conditions as the chapters move on.

Downs builds up the models with the assumptions. We make derivations from the model. Then we kind of start relaxing those assumptions and see how the predictions change.

Chapter 1:

Chapter 1 seems to be justifying why we should study government through a economic rationality and what that entails (assumptions, etc.)

Goal: We want to predict behavior! Economic rationality is a tool/lens to help us predict rational and irrational behavior.

As opposed to government’s impact on private decision making or the share of government in economic aggregates, Downs makes the point that government has not been successfully integrated with private decision-makers in a general equilibrium theory.

Thesis: Provide a behavior rule for democratic government.

- Provide such a rule by positing that democratic governments act rationally to maximize political support.

What is economic rationality?

A rational man is one who behaves:

1) always makes a decision

2) he ranks all alternatives in order of preferences.

3) preference ranking is transitive

4) always chooses that which ranks highest in his preference

5) always makes the same decision each time he is confronted with the same alternatives

these assumptions are applied to all the players: political parties, interest groups, and governments.

Rationality: refers to the process of action, not to their ends or even to their success at reaching desired ends.

Are inefficient men always irrational or can rational men also act inefficiently?

a mistaken rational man at least intends to strike an accurate balance between costs and returns; whereas an irrational man deliberately fails to do so.

rational man corrects mistake if known and the cost of eliminating it is smaller than the benefits therefrom.

if a man exhibits political behavior which does not help him attain his political goals efficiently, we feel justified in labeling him politically irrational, no matter how necessary to his psychic adjustments this behavior may be.

The Structure of the Model

Our model is based on the assumption that every government seeks to maximize political support.

periodic elections are held

primary goal is reelection

the election is the goal of those parties now out of power.

party that receives the most votes controls the entire government until the next election.

no intermediate votes

governing party has unlimited freedom of actions.

government cannot hamper the operations of other political entities. (or freedoms)

No economic limits to its power.

With these assumptions, we can construct a model showing how a rational government behaves in the kind of democratic state we outlined above.

There is uncertainty in our “world”.

- uncertainty = imperfect information.

“Thus our model could be described as a study of political rationality from an economic point of view. By comparing the picture of rational behavior which emerges from this study with what is known about actual political behavior, the reader should be able to draw some interesting conclusions about the operation of democratic politics.”

The Relation of our Model to Previous Economic Models of Government

This is kind of the warrant section for the article? Why do we need a new model? What do others do and why are they insufficient?

Previous models are normative.

Downs model is positive. - deductive

Downs discusses previous models, mainly focusing on Buchanan-Samuelson approach

Samuelson posits two mutually exclusive ways to view decision making by the state:

1) consider the state a separate person with its own ends not necessarily related to the ends of the individuals

- Downs disagree with this

2) only individuals as having end structures. The state has no welfare function of its own; it is merely a means by which individuals can satisfy some of their wants collectively.

Downs thinks this is partly true.

- the individualistic view is incomplete because it doesn’t take coalitions into consideration.

Problem: discovering a relationship between the ends of individuals at large and the ends of the coalition which does not restrict government to providing indivisible benefits. p.17

Our model attempts to forge a positive relationship between individual and social end structures by means of a political device.

in our model, government pursues its goal under three considerations:

a democratic political structure which allows opposition parties to exist

an atmosphere of varing degrees of uncertainty,,

and an electorate of rational voters.

We wish to discover what form of political behavior is a rational for the government and citizens of a democracy.

Chapter 2: Party Motivation and the Function of Government in Society

Theoretical models should be tested primarily by the accuracy of their predictions rather than by the reality of their assumptions.

- interesting general point.

Anand just provides one page of chapter 2 lol

Chapter 3: The Basic Logic of Voting

In order to plan its policies so as to gain votes, the government must discover some relationship between what it does and how citizens vote.

This is derived from the axiom that citizens act rationally in politics!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

This implies that each citizen casts his vote for the party he believes will provide him with more benefits than any other.

Need to show what rational voting implies.

Utility Income From Government Activities

Utility is a measure of benefits in a citizen’s mind which he uses to decide among alternative courses of action.

- a rational man always takes the one which yields him the highest utility.

Citizens are utility maximizers.

Government activity provides a utility income to citizens.

includes benefits they know and do not know they are receiving.

- however, only benefits which voters become conscious of by election day can influence their voting decisions; otherwise their behavior would be irrational.

The Logical Structure of the Voting Act

Terminology of the analysis:

unit of time: election period.

- time elapsed between elections.

The Two Party Differentials:

each voter votes for the party they believe will provide him with a higher utility income than any other party during the coming election period.

- to find this, they compare the utility incomes they believe they would receive from each party.

\[E(U^A_{t+1}) - E(U^B_{t+1})\]

this is the expected party differential

if positive: vote incumbent

if negative: vote opposition

if zero: abstain.

A rational voter bases their view of the future off the past/present.

thus what is most important is the CURRENT party differential.

- utility the individual earned from the party at time \(t\)

The Trend Factor and Performance Ratings:

Trend factor: the adjustment each citizen makes in his current party differential to account for any relative trend in events that occurs within the current election period.

When the individual cannot see any difference between the two parties running

to escape this, they alter their decision to whether or not the incumbents have done as good a job governing as did their predecessors in office.

- reminds me of a nature of the times voter in some fashion.

Rational men are not interested in policies but in their own utility incomes.

Performance ratings become a thing when the individual things the parties are the same.

Preliminary Difficulties Caused By Uncertainty

The world doesn’t have complete and costless information

- there is uncertainty!

Individual can only estimate their utility income.

They will base them upon those few areas of government activity where the difference between parties is great enough to impress them.

Downs excludes deliberate misinformation/disinformation.

Downs assumes political tastes are fixed and only new information can change their mind.

Variations in Multiparty System

same thing applies only the individual compares the incumbent against multiple parties.

However, a rational voter not may vote for their preference because they another party may have a better chance of winning.

An important part of voting is predicting how other citizens will vote by estimating their preferences.

Lazarsfeld et al. 1944. The People’s Choice. Prefaces; Chapters 1-3; 6.*

Lecture Notes:

Community study.

panel study - changes over time.

A contained social setting by rooting the study in Erie.

Design: Survey/community

- Designed to see how people change between the elections.

Question: How do attitudes form? Do campaigns actually work? Social group influence? Context!?

- How do we situate individuals in context?

Politics has gotten nationalized today - which is different from Lazarsfeld time.

They are going to look at social groups and the salience of social groups.

- think about the different variables.

you can see the origin of identity politics in this reading.

How they set this up is a good way to set up your papers and the further complicate the story.

Theory contribution: the role of cross-pressures.

- sociological

Columbia is social approach

- big contribution is cross-pressure.

Michigan is social psychological

Why does this matter?

- the parties are becoming a social identity.

Social groups and party id is the same. - liliana mason

- this is the difference today.

academic ambivalence - it is struggling between competing considerations

- it does not mean indifferent!

This work is important because it establishes political communication, information flow, media effects,

- they did not find a big influence of radio and newspaper on vote choice.

Preface:

The People’s Choice is focused on the formation, change, and development of public opinion.

- how do attitudes form?

the role of turnover in the election. turnover represents opinion/behavior is unstable (if large).

Lazarsfeld et al. asks some interesting rhetorical questions:

What types of events show a small or large turnover as they develop?

Does the turnover tend to become smaller as the events run their course?

At what point is a minimum turnover reached and what is likely to increase it again?

Under what conditions do we have a balanced turnover, as in this case, where the changes in various directions seem to cancel each other?

- all of these kind of remind me of Gelman & King’s article on polls/elections/campaigns.

Turnover is the result of changes which come about in the intentions, expectations, and behavior of individual persons.

Three questions arise

What kind of people are likely to shift?

Under what influences do these shifts come about?

In what directions are the shifts made?

“In the present study, face-to-face contacts turned out to be the most important influences stimulating opinion change.

- “The discovery of the conditions under which attitudes or modes of behavior are particularly accessible to personal influence, the classification of types of personal influence most effective in modifying opinion, the examination of situations in which the more formal influences of mass media seem to produce change, all these are typical problems for what we have called dynamic social research.” xxvi

xxvi is very interesting overview. Definitely come back here.

“We thus came to the conclusion that party changes are in the direction of greater consistency and homogeneity within subgroups. p.139”

Making an argument that in 1944, there was greater democratic machinery in Erie, causing more to side with democrats as opposed to 1940 which saw more side with republicans when their machinery was stronger.

FUTURE STONE: XXXII -XXXIII YOU NEED TO READ AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN. IT IS INCREDIBLY SUCCINT.

- discussion about cross-pressure, information gathering, social bridging, etc.

individuals who experienced cross-pressures took considerably longer to arrive at a definite vote decision.

“In the present study we found that one of the functions of opinion leaders is to mediate between the mass media and other people in their groups. It is commonly assumed that individuals obtain their information directly from newspapers, radio, and other media. Our findings, however, did not bear this out. The majority of people acquired much of their information and many of their ideas through personal contacts with the opinion leaders in their groups. These latter individuals, in turn, exposed themselves relatively more than others to the mass media.

Chapter 1:

Goal: Discover how and why people decide to vote as they did.

- What were the major influences upon them during the campaign of 1940?

Focus: development of an individuals vote during the campaign.

- this is going to bring up additional questions about attitude formation more broadly.

Data: Panel data - this is new at the time.

Survey data: individuals living in Erie county, Ohio 1940/1944.

600 people - stratified sampling.

they were aware of interview frequency biasing results! back in 1940?!

would have liked the poll to have an extra month before the conventions.

different panels with different frequency of interviews.

Chapter 2:

Describes the county of Erie.

goal is to know why people voted the way they did.

Sandusky - church was a major factor in life.

mixed industrial and agriculture type.

labor as a political bloc was not very strong.

Not a lot of solidarity among the ethnic groups within the county,

1940 - republican campaign was more organized in the county than democrats,.

proceeds to list important local, national, and international events for each half of the month.

- This is interesting and I think works because the information flow is so much less than what we have now.

Chapter 6: Time of Final Decision

Why do people decide who to vote for at different times?

Delayed decision - had less interest in the election

those who made their choice late - subject to more cross-pressures.

more interest = the sooner they decide who to vote for.

- they were also more likely to express anxiety.

this all is very similar to Campbell.

Those who decide late were also less concerned about the ramifications of the election and who won.

What cross-pressure will win out? That is which has more influence - religion or socio-economic status?

The different cross-pressures analyzed:

Religion and SES level

Occupation and Identification

1936 and 1940 Vote

The voter and his family

the voter and his associates

1940 Vote Intention and attitude Toward Business and Government

Why did people subject to cross-pressures delay their final decisions as to how they should vote?

the single biggest factor in delaying vote was the lack of complete agreement within the family.

second, some are waiting for “events” to resolve the conflicting pressures

I wonder how this squares with Gelman & King

- need to revisit that.

“We will recall that the people who make up their minds last are those who think the election will affect them least.” p.61

“Our hypothesis that the person or the party that convinces the hesitant voter of the importance of the election to him personally-in terms of what he concretely wants-can have his vote.” p.61

- we know from previous lit that, the voter might not know concretely what they want.

As the number of cross-pressures increases, the degree of interest shows a steady decline.

this is interesting. I wonder why this is.

maybe cross-pressures make it harder for the individual to realize the “fundamentals”.

Week 3: Political Knowledge

Lecture Notes:

The readings are all wrestling between the effect of individual level features and/or environmental levels on political knowledge acquisition.

If you critique all readings - make sure you broaden the claim.

Main Question: Does the public have enough knowledge?

Main Question: What do we mean when we say a “knowledgeable public”?

What does the public know?

facts?

who is in government?

current events

processing/synthesizing info.

- critical thinking skills.

Knowledge -> participation

Access to information to have knowledge.

Quality of information -> Decisions?

Mondak likes jazz. Also read for the “don’t know” argument.

If the public is dumb, what might save them?

Heuristics!

- but also bias and a mixed bag.

Correct voting. Does your vote match your preferences.

political knowledge = factual things - timeless/timely

political sophistication: combo of interest and awareness - zaller invention - interest + factual knowledge. kinda an index measure.

Simple to heterogeneity

vairation in question types

different variation in person types of who can get knowledge

personality/dispositions effect knowledge.

Barabas, Jason, Jennifer Jerit, William Pollock, and Carlisle Rainey. 2014. “The Question(s) of Political Knowledge.” American Political Science Review. 108:840-855.

Lecture Notes:

survey issues with political knowledge questions.

building into their model that some knowledge model questions are different than others and more difficult.

- not all tasks are equal.

multilevel modeling

- allow certain parameters to vary across question types.

dangerous to talk about knowledge in monolithic terms.

Abstract:

Political knowledge is a central concept in the study of public opinion and political behavior. Yet what the field collectively believes about this construct is based on dozens of studies using different indicators of knowledge. We identify two theoretically relevant dimensions: a temporal dimension that corresponds to the time when a fact was established and a topical dimension that relates to whether the fact is policy-specific or general. The resulting typology yields four types of knowledge questions. In an analysis of more than 300 knowledge items from late in the first decade of the 2000s, we examine whether classic findings regarding the predictors of knowledge withstand differences across types of questions. In the case of education and the mass media, the mechanisms for becoming informed operate differently across question types. However, differences in the levels of knowledge between men and women are robust, reinforcing the importance of including gender-relevant items in knowledge batteries.

Bumper Sticker:

- Political knowledge is not as simple as we think.

Research Question:

What determines who is informed?

How does the temporal dimension relate to knowledge acquisition

Hypothesis:

Levels of knowledge for recent facts should be lower relative to facts that were established years or decades ago because there have been fewer opportunities for people to acquire such facts.

We expect that level of education will have a stronger (and more positive) relationship to general measures of political knowledge than it does to policy-specific knowledge.

We hypothesize that the effect of mass media on knowledge varies along the temporal dimension on figure 1.

- we expect to observe a positive relationship between the amount of media coverage and surveillance facts, but little or no relationship between the level of media coverage and static facts.

The knowledge gap between men and women will be smaller for gendered questions compared with nongendered questions in each of the four cells.

Background:

The present study provides a framework for understanding how the content or type of question affects observed levels of knowledge.

Political Knowledge - Delli Carpini & Keeter’s definition - “The range of factual information about politics that is stored in long-term memory.

How does this differ from political sophistication?

- keep this in mind.

3 factors:

ability

opportunity

motivations

How is a fact learned?

first factor: how recently the fact came into being

second factor: the type of fact - whether the question has to do with public policy concerns or the institutions and people/players of government (topical dimension).

General v. policy

General - questions ask about the institutions and people/players of government

- Carpini and Keeter emphasize the importance of general.

Policy-specific - whether the question has to do with public policy concerns

Gilens strong advocate

- “many people who are fully informed in terms of general political knowledge are nonetheless ignorant of policy-specific information that would alter their political judgments.”

policy specific is more domain-specific than general

thus harder to acquire.

- thus need greater motivation to acquire that information.

What We Know About Political Knowledge:

Ability - level of education

Education was the “strongest single predictor of knowledge”

education has a direct effect on political knowledge and an indirect effect through political engagement and structural factoprs such as occupation and income.

most schools teach about institutions and processes of government.

- empirical analysis mostly looks at general political knoweldge.

we expect that level education will have a stronger (and more positive) relationship to general measures of political knowledge than it does to policy specific knowledge

Opportunity - the amount of news coverage

more information available.

Delli Carpini, Keeter, and Kennamer find that people living close to the capitol are more knowledgeable about state politics than those living farther away.

- interesting! Is this a media story though? Or is this a geographical/physical interaction story?

The level of political knowledge increases as information about particular topics becomes more plentiful

there is an assumption here, that this information is “correct”.

are we testing solely on events?

Motivation - self- or group-interest

gender gap in political knowledge.

why?

might be because of the question we ask.

women have much great knowledge when the question has direct relevance to women as a group.

mechanism: women have higher levels of knowledge on “Gendered” questions as a result of the instrumental benefits of learning particular facts.

Data and Methods:

Original dataset

lots of observations (tens of thousands)

surveys were augmented with media content data and other controls.

Depedent Variable: Knowledge

Pew research and Roper archives for surveys about knowledge in the later half of the 2000s

questions about public policy, people in office, etc.

Independent Variables: Question and Environmental level indicators

Each knowledge question was coded for the two question-level characteristics appearing in fig 1. (surveillance vs. static and policy-specific vs. general).

temporal dimension: when the even occured - when the fact became established.

- when the person took office. When the bill passed. Last measure of unemployment prior to the question being asked in the survey.

surveillance facts were treated as those in which the correct answer was established 100 days prior to survey. all other questions were coded as static.

43% surveillance and 57% static

Questions haveing to do with institutions of gov or people and players were coded as zero

- domestic policies, actions by congress, or foreign policy topics = 1

To examine the effect of mass media on knowledge, we characterized the info environment for each topic.

Use the Pew Research News Coverage Index (NCI) project.

provides a broad snapshot of which stories are being reported in the media at a given time and by who.

- The media coverage variable is the NCI count of stories concerning a given knowledge question extending six weeks back in time. Thus, for a question asking which office Hillary Clinton holds in the beginning of June 2010, we counted NCI stories having to do with Hillary Clinton from roughly the middle of April until the field date of the survey. The six-week cutoff, though somewhat arbitrary, ensures that potential learning effects of current coverage are not misidentified due to less relevant levels of coverage in the past.

Also have individual level indicators

edu range from 1 (least) to 8 (most)

income

age

gender

race

partisanship

they used multiple imputation and averaged.

Result:

unit of analysis: a person’s response to a knowledge question.

logit model - outcome : which is the probability that individual i answers question j correctly.

- a function of individual-level and question-level characteristics.

use random effects because to account for question clustering given by the same individual in survey questions.

They use fixed effects for certain \(\beta_j\) which is income, age, black, democrat, and republican

\(n_j\) represent question level random effects - which allow the effect of gender and education to vary across questions.

\(a_i\) signifies an individual level random intercept (interpreted as the variation in individuals political knowledge)

- I thought this is our DV???????

\[ Pr(y_{ij}=1)=logit^{-1}(a_i+n^{cons}_j +n^{edu}_jEducation_i + n^{fem}_jFemale_i+\beta_{inc}Income_i+\beta_{age}Age_i+\beta_{black}Black_i+\beta_{dem}Democrat_i+\beta_{rep}Republican_i) \]

First difference: represents how the probability of a correct answer changes as an explanatory variable moves from one substantively meaningful value to another.

The Effect of Education:

increasing education has a higher effect for general facts rather than for policy facts.

probability of getting the correct answer to a static-general knowldge question increases with education. This is bigger than static policy question

people with the most education remain ignorant of certain policy facts.

“Level of education is positively related to knowledge in all four quadrants, but there are statistically significant differences in the strength of that relationship, precisely in the manner we expect.”

Learning from Media Coverage:

recall the second hypothesis: the positive relationship between news coverage and knowledge stablished by previous studies will be largely confined to surveillance facts.

more news -> more knowledge of surveillance facts.

more news not equal to more knowledge of static facts.

Observe a large effect from a low to high media environment on surveillance-general facts is large.

Observe a null effect on surveillance-policy facts.

The Gender Gap

- smaller knowledge gap between genders on gendered questions.

Discussion:

Education does not confer the same benefits across different types of questions.

Mass media effect is largely confined to recent facts.

gender knowledge gap is smaller when questions are gendered.

We should include knowledge questions along with the standard set of demographic items in all opinion survey.

Bartels, Larry. 2007. “Homer Gets a Warm Hug: A Note on Ignorance and Extenuation.” Perspectives on Politics. 5(4): 785-790.

Lecture Notes:

- Bartels says voters are misguided and ignorant.

Abstract:

Lupia, Levine, Menning, and Sin show that well-informed Republicans and conservatives were highly supportive of the 2001 Bush tax cut. They mistakenly infer that this fact invalidates my claim in “Homer Gets a Tax Cut” that “the strong plurality support” for the tax cut was “entirely attributable to simple ignorance.” Their analysis, like mine, implies that a fully-informed public would have been lukewarm, at best, toward the tax cut. They have little to say about why this is the case, beyond insisting that “citizens have reasons for the opinions they have.” I suggest that citizens’ “reasons” are sometimes misleading, misinformed, or substantively irrational, and that social science should not be limited to “attempts to better fit our analyses into their rationales.”

Background:

Bartels wrote “Homer Gets a Tax Cut”.

Lupia, Levine, Menning, and Sin write an article where they disagree with the findings. They claim Bartels’ makes an improper assumption.

- Liberals with more info did not support tax cuts while Rep with more info increased support of tax cuts.

Debate about information effects on republicans/conservatives supporting Bush tax cuts.

According to Lupia, Levine, Menning, and Sin, more informed republicans were roughly similar to less informed republicans on their views of tax cuts.

- they found more informed dems v. less informed dems had a higher divergence.

NES 2002 is not as reliable as other years. It was kinda bad this year.

I certainly agree with Lupia, Levine, Menning, and Sin’s key claim that political information may have different effects on different people.

Debate:

Bartels agrees with Lupia et al.’s claim that political information may have different effects on different people

They disagree on the “implications of this heterogeneity for my conclusions about the bases of support for the Bush tax cut.”

this is a mouthful.

- they disagree over the conclusions about what Bartels has to say about people who support the Tax cut.

“The fact that ideological and partisan disagreements about the tax cut only emerged clearly among relatively well-informed people will come as no surprise”

I think he is basically saying that this is obvious and this is what Zaller shows.

- THIS IS THE KEY POINT: “IN THE CASE OF THE BUSH TAX CUT, HOWEVER, UNINFORMED CITIZENS REGARDLESS OF THEIR POLITICAL VALUES WERE VERY LIKELY TO SUPPORT THE POLICY-IF THEY TOOK ANY POSITION AT ALL.

Much of Lupia, Levine, Menning, and Sin’s critique focuses on my claim that “the strong plurality support for Bush’s tax cut … is entirely attributable to simple ignorance.”

It does suggest that a fully-informed citizenry would have been lukewarm toward the tax cut, at best. Is that fact relevant to understanding

Bartels examines a variety of potential bases of public support for the Bush tax cut

Bartels argues they basically paraphrase his same argument.

Their analysis, like mine, implies that a fully-informed public would have been lukewarm, at best, toward the tax cut. They have little to say about why this is the case, beyond insisting that “citizens have reasons for the opinions they have.” I suggest that citizens’ “reasons” are sometimes misleading, misinformed, or substantively irrational, and that social science should not be limited to “attempts to better fit our analyses into their rationales.”

Lupia et al. unsubtle effort to, quite literally, change the subject is in service of a broader goal: rationalizing every political thinking and behavior.

the heart of their argument is that “citizens have reasons for the opinions they have”, and that we as social scientists should “conduct scholarship that attempts to better fit our analyses into their rationales.”

Bartels agrees we need to understand people’s rational. HOWEVER:

he seems to be arguing that these authors are making the point that all citizens can rationalize the opinions they have.

it is this that he disagrees with:

- “However, decades of psychological research have amply demonstrated that people’s subjective understandings of their own behavior are often incomplete, predictably biased, and sometimes highly misleading.

This does not mean well-informed people should always be considered substantively rational.

Here, as in many other instances, better-informed people seem mostly to have grasped the biased world-view of “their” political elites rather than an accurate perception of real social conditions

- YES I AGREE!

Delli Carpini, M. and S. Keeter. 1996. What American Know about Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press. Chapters 2-4*(skim)

we don’t really know what people know - thus we get this book

big debate about whether we should give “don’t know” options.

Chapter 2:

How much info does the American public have on politics is like the biggest question.

people ought to know the structure of government and its basic elements.

“The democratic citizen is expected to be well-informed about political affairs. He is supposed to know what the issues are, what their history, what the relevant facts are, what alternatives are proposed, what the party stands for, what the consequences are.”

- lol

Three broad areas of political knowledge:

the rules of the game

the substance of politics

people and parties.

“None of this relieves citizens of their individual responsibility to be informed, but it suggests that an informed citizenry requires not only will, but also opportunity.”

- interesting point.

Chapter 3: Stability and Change in Political Knowledge

Ability, motivation, opportunity.

Tension between looking to the past and looking to the future.

Americans are essentially no more nor less informed about politics than they were fifty years ago.

we should expect more edu -> civic ability and understanding

- this isn’t necessarily true.

For Neil Postman, the dominance of television as the central form of public discourse has reduced teaching to “an amusing activity,” as children and young adults increasingly demand to be entertained rather than education (1985)

- like this quote. Certainly has gotten worse!

Decline in education related to the progressive movement?

they say we don’t emphasize the accumulation of facts enough?

- I need to dig into this a bit more. Not sure how i feel.

education teaches you how to acquire info and provides substantive info.

workplace is important too

“perhaps the greatest opportunity to learn about politics is provided by the mass media.”

“The greatest contribution of electronic media to democracy should occur in the widespread distribution of public-affairs information to citizens. In a sense, most of the provisions under which media operate in democratic societies are intended to achieve this fundamental goal…”

lol.

And Barber argues that “the capabilities of the new technology can be used to strengthen civic education, guarantee equal access to information, and tie individuals and institutions into networks that will make real participatory discussion and debate possible across great distances”

- LOL

“Henry David Thoreau’s Walden:”We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate….”

Postman and others also argue that electronic media are unsuited for the kind of rational argumentation and deliberation required in democratic discourse

YES!

p.113

read it.

- “A related concern is that the seductive nature of television —the ease with which it can be watched, its entertaining and visually arresting format—is driving citizens away from newspapers and magazines, while at the same time forcing the print media to compete by turning to shorter, less demanding stories and the use of such techniques as color graphics.

Perhaps the greater nationalization of politics is because citizens are increasingly motivated to follow national politics - creating a cycle.

Chapter 4:

“For example, whereas partisans are more informed than nonpartisans, strong republicans are significant more informed than are strong Democrats.”

the survey was in 1989

I wonder if timing has to do with this.

There is a connection between interest and knowledge that is going untested

I wonder if Democrats decrease in their political interest when they are in control

Republicans subsequently may increase their political attention/interest when the outparty is in office

- Taber and Lodge argument being made here.

“Political learning is affected not only by individual factors, such as one’s interest in politics, but also-and often profoundly- by forces external to the individual: the information environment and more, generally, the political context in which learning occurs.”

Lau, Richard P., and David P. Redlawsk. 2001. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making.” AJPS . 45:951-71.

Abstract:

This article challenges the often untested assumption that cognitive “heuristics” improve the decisionmaking abilities of everyday voters. The potential benefits and costs of five common political heuristics are discussed. A new dynamic processtracing methodology is employed to directly observe the use of these five heuristics by voters in a mock presidential election campaign. We find that cognitive heuristics are at times employed by almost all voters and that they are particularly likely to be used when the choice situation facing voters is complex. A hypothesized interaction between political sophistication and heuristic use on the quality of decision making is obtained across several different experiments, however. As predicted, heuristic use generally increases the probability of a correct vote by political experts but decreases the probability of a correct vote by novices. A situation in which experts can be led astray by heuristic use is also illustrated. Discussion focuses on the implications of these findings for strategies to increase input from under-represented groups into the political process.

Research Question:

What are the individual and contextual determinants of heuristic use?

Does the use of heuristics affect (without prejudging whether it improves or hinders) the quality of political decision making

Five Political Heuristic:

Party affiliation

candidate’s ideology

Endorsements

polls

- provide “viability” info

Candidate appearance

- Dukakis in the tank.

Hypothesis:

we hypothesize that the use of cognitive heuristics generally will be associated with higher quality decisions

we expect heuristic use to be most efficacious for political experts

the use of cognitive heuristics will interact with political sophistication to predict higher quality decisions

Method:

- scrolling for info.

Lupia, Arthur et al. 2007. “Were Bush Tax Supporters ‘Simply Ignorant?’ A Second Look at Conservatives and Liberals in ‘Homer Gets a Tax Cut.”’ Perspectives on Politics. 5(4): 773-784.

Abstract:

In a recent issue of Perspectives on Politics, Larry Bartels examines the high levels of support for tax cuts signed into law by President Bush in 2001. In so doing, he characterizes the opinions of “ordinary people” as lacking “a moral basis” and as being based on “simple-minded and sometimes misguided considerations of self interest.” He concludes that “the strong plurality support for Bush’s tax cut … is entirely attributable to simple ignorance.”

Our analysis of the same data reveals different results. We show that for a large and politically relevant class of respondents, conservatives and Republicans, rising information levels increase support for the tax cuts. In fact, Republican respondents rated “most informed” supported the tax cuts at extraordinarily high levels (over 96 percent). For these citizens, Bartels’ claim that “better-informed respondents were much more likely to express negative views about the 2001 tax cut” is untrue. Bartels’ results depend on the strong assumption that if more information about the tax cut makes liberals less likely to support it, then conservatives must follow suit. Our analysis allows groups to process information in different ways and can better help political entrepreneurs better reconcile critical social needs with citizens’ desires.

Question:

How does information acquisition (and to what level) influence support/opposition to policies?

Are voters stupid? RE: Bartels

Bartels Argument:

Bartels claims that “better-informed respondents were much more likely to express negative views about the 2001 tax cut”

He argues that if Americans had been more enlightened, greater numbers would have opposed the cuts.

Bartels characterizes the opinions of “ordinary people” as being superficial and based on “simple-minded and sometimes misguided considerations of self-interest.”

“Finally, and most importantly, better-informed respondents were much more likely to express negative views about the 2001 tax cut…If we take this crossectional difference in views as indicative of the effect of information on political preferences, it appears that the strong plurality for Bush’s tax cut…is entirely attributable to simple ignorance.”

Week 4: Ideology/Sophistication

Lecture Notes:

The broad question (in my POV) is about if, when, and why do people have constraints on their belief system

- this is the throughline (so far).

we are seeing a pattern through all this research on the masses.

the most sophisticated at every level are influenced the most in general.

they use heuristics better

they are more interested

more constraints

more active

etc.

- nothing seems to move the bottom of the masses.

What moves the lower strata politically

what does the lower strata even think?

what brings them into the political process.

Are voters making right decisions?

- do they know what they are doing?

Thinking about top-down elite info transfer.

tourangeau et al. is good.

executive functioning(?)

Opinions: verbal expression of an attitude

attitude: an enduring predisposition to respond

- opinions are imperfect indicators of underlying, unobserved attitudes.

Experiment:

randomization

can control the IV

Achen, C.H. 1975. “Mass Political Attitudes and the Survey Response.” American Political Science Review. 69: 1218-31.

Abstract:

Students of public opinion research have argued that voters show very little consistency and structure in their political attitudes. A model of the survey response is proposed which takes account of the vagueness in opinion survey questions and in response categories. When estimates are made of this vagueness or “measurement error” and the estimates applied to the principal previous study, nearly all the inconsistency is shown to be the result of the vagueness of the questions rather than of any failure by the respondents.

Bumper Sticker:

Survey design can lead to different results!

Also, Converse missed some important methods considerations.

Research Question:

- What are possible sources for why there is weak correlation among citizens’ political survey responses?

Background/Theory:

“There can be little doubt that the sophisticated electorates postulated by some of the more enthusiastic democratic theorists do not exist, even in the best educated modern societies”

Beliefs may be best expressed on a continuum.

We use likert scales but these are discrete representations of a continuous preference.

As a result, it is unsurprising this leads to respondents appear to be inconsistent in their beliefs.

We usually just chalk this up as measurement error

Achen: “…it reflects a flaw in the survey research method rather than in responses of subjects.”

- He argues Converse did not contend with these issues and thus underestimates voters’ attitudinal stability.

There are two theories about instability in respondents political survey questions:

1) voters actually have instability in their opinions/belief system.

- This is Converse’s argument

2) low reliabilities of opinion survey question

- This is Achen’s argument contribution.

BIG ISSUE FOR ACHEN: the vagueness of the questions asked.

Data/Method:

Converse’s data

1132 respondents

“When a voter is stable in his views and all observed variability is measurement error, correlations will be equal across time periods. At the other extreme, when a voter is unstable and there is no measurement error, correlations should become smaller at a predictable rate as time periods become more distant from each other.”

Basically:

smaller correlations between periods means genuine changes in belief.

- time 1 should NOT have more predictive power than time 2 for time 3

consistent beliefs means that time 1 or time 2 should not be better than the other at predicting time 3.

- correlation is equal across time periods!

I am a bit confused by the model - \(p_t\) represents the actual opinion at time t of the respondent. But we cannot know this? We only have the observed opinion represented at \(x_t\)

Results:

Voters’ beliefs are a bit more stable than we thought

- this does not mean voters have more wisdom.

This article says nothing about a voter’s sophistication

- only that there beliefs are a bit more stable than what Converse initially articulated.

“Here the problem with the weak original correlations is demonstrated to lie, not with the variability of respondents, but rather with the fuzziness of the questions and with other errors of measurement.”

This only works for panel data I think.

The simplicity of questions and the fact that respondents might have preferneces on a continuum that don’t perfectly map onto the likert scale categories that might be driving this “measurement error.”

Need to figure this out.

how does the question get interpreted by different individual factors?

measurement error is DV

IV = independent variables - Education/income.

should expect “better-off” members of the electorate to have lower expected measurement errors.

there are a lot more IVs.

However, they find that these individual factors have little to no predictive power in explaining measurement error. ACCORDING to R^2

- WHO GIVES A SHIT ABOUT r^2. Author says the same thing

Factors that are are significant: note their coefficient (effect) is still quite small.

taking an interest in the campaign

caring who wins

talking to others about it

city dweller is not a significant variable

- keep this in your backpocket for your research.

higher education

income

occupational status

The well-informed and interested have nearly as much difficulty with the questions as does the ordinary man. Measurement error is primarily a fault of the instruments, not of the respondent

Converse, P. 1964. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics.” In Apter, ed. Ideology and Discontent. New York: The Free Press.*

Chapter Reading: The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics

Focus: measurement strategies for belief systems.

- “Our focus in this article is upon differences in the nature of belief systems held on the one hand by elite political actors and, on the other, by the masses that appear to be “numbered” within the spheres of influence of these belief systems.

Thesis: There are important and predictable differences in ideational worlds as we progress downward through such “belief strata” and that these differences, while obvious at one level, are easily overlooked and not infrequently miscalculated.

They don’t like “ideology”

Belief System: a configuration of ideas and attitudes in which the elements are bound together by some form of constraint or functional interdependence.

Constraint: the success we would have in predicting, given initial knowledge that an individual holds a specified attitude, that he holds certain further ideas and attitudes.

basically logical constraint is what they are getting at.

- but there are others.

Centrality: idea elements within a belief system vary in a property we shall call “centrality”, according to the role that they play in the belief system as a whole.

II. Sources of Constraint on Idea-Elements

logical inconsistencies are far more prevalent in broad public.

classical logic: if x then y. or this must follow if z.

Psychological Sources of Constraint

not classically logical.

Seems to be driving at a sort of cultural constraint.

the “logic of culture”. morals/ethics

“What is important is that the elites familiar with the total shapes of these belief systems have experienced them as logically constrained clusters of ideas, within which on part necessarily follows from another.”

Consequences of Declining Information for Belief Systems

Primary Thesis: as one moves from elite sources of belief systems downwards on such an information scale, several important things occur:

1) the contextual grasp of “standard” political belief system fades out very rapidly.

- constraints decline across the universe of idea-elements.

2) The character of objects that are central in a belief system undergoes systematic change.

these objects shift from the remote, generic, and abstract to the increasingly simple, concrete, or “close to home”.

Interest paragraph - i don’t know if I buy this:

- “Such observations have impressed even those investigators who are dealing with subject matter rather close to the individual’s immediate world: his family budgeting, what he thinks of people more wealthy than he, his attitudes toward leisure time, work regulations, and the like. But most of the stuff of politics-particularly that played on a national or international stage- is, in the nature of things, remote and abstract. Where politics is concerned, therefore, such ideational changes begin to occur rapidly below the extremely thin stratum of the electorate that ever has occasion to make public pronouncements on political affairs. In other words, the changes in belief systems of which we speak are not a pathology limited to a thin and disoriented bottom layer of the lumpenproletariat; they are immediately relevant in understanding the bulk of mass political behavior.” p.213 towards the bottom.

III. Active Use of Ideological Dimensions of Judgment.

Different levels:

ideologue

- respondents who did indeed rely in some active way on a relatively abstract and far-reaching conceptual dimension as a yardstick which political objects and their shifting policy significance over time were evaluated.

semi-ideologue

- respondents who mentioned such a dimension in a peripheral way but did not appear to place much evaluative dependence upon it or who used such concepts in a fashion that raised doubt about the breadth of their understand of the meaning of the term.

Group interest

- respondents who failed to. rely upon any such over-arching dimensions yet evaluated parties and candidates in terms of their expected favorable or unfavorable treatment of different social groups in the population.

Nature of the times

- democrats made economy bad i vote republican now.

Nonsensical

- voters who just said random stuff basically.

V. Constraints among Idea-Elements.

more sophisticated = more constraints.

mass public does not share ideological patterns of belief with relevant elites at a specific level any more than it shares the abstract conceptual frames of reference.

Freeder et al. 2019. “The Importance of Knowing”What Goes with What”: Reinterpreting the Evidence on Policy Attitude Stability.” Journal of Politics. 81(1).

Abstract:

What share of citizens hold meaningful views about public policy? Despite decades of scholarship, researchers have failed to reach a consensus. Researchers agree that policy opinions in surveys are unstable but disagree about whether that instability is real or just measurement error. In this article, we revisit this debate with a concept neglected in the literature: knowledge of which issue positions “go together” ideologically—or what Philip Converse called knowledge of “what goes with what.” Using surveys spanning decades in the United States and the United Kingdom, we find that individuals hold stable views primarily when they possess this knowledge and agree with their party. These results imply that observed opinion instability arises not primarily from measurement error but from instability in the opinions themselves. We find many US citizens lack knowledge of “what goes with what” and that only about 20%–40% hold stable views on many policy issues.

Bumper Sticker:

Research Question:

What share of citizens hold meaningful views about public policy?

What is the source of instability in survey measures of the public’s policy opinions?

Hypothesis:

The knowledge of what goes with what plays an important and under-appreciated role in attitude stability.

- When people learn what goes with what (which policy positions are Republican and which are Democratic), they will tend to exhibit stable policy views.

Those who do not know elite positions should generally have less stable views, even when we measure their attitudes with multi-item scales.

Background/Theory:

Debate in lit about question

Zaller & Zaller & Feldman argued that opinion instability results from citizens holding conflicting considerations on policy issues and then sampling from these pools of inconsistent considerations when they answer survey questions.

Others argue (Achen) that people do hold meaningful opinions but is ambiguous due to measurement error.

If citizens lack meaningful views about even the most salient political issues, instead having their opinionsontheseissueseasilychangedbypoliticalelites and the media, “democratic theory loses its starting point” (Achen 1975, 1220).

In this article, we show that this long line of research has yielded mixed results because it has examined opinion stability by general political knowledge, a poor proxy for what we believe drives attitude stability.

- what goes with what

People adopt the heuristics and follow the leaders

- very top-down driven mechanism for attitude stability.

Data/Method:

Results:

- We find that a large segment of the public lacks knowledge of “what goes with what,” and consequently a large segment lacks stable policy views on salient issues. Relatedly, we find that those who do possess this knowledge tend to have stable views, but only when they agree with the views of their party.

Huckfeldt, Levine, Morgan and Sprague. 1999. “Accessibility and the Utility of Partisan Ideological Orientations.” American Journal of Political Science. 43(3): 888-912.

Abstract:

We examine the accessibility of ideological and partisan orientations as factors affecting the political capacity of citizens. In particular, is the utility of partisan and ideological reasoning contingent on the accessibility of an individual’s own self-identifications? Are people with accessible points of ideological and partisan orientation more likely to in voke these orientations in formulating political judgments and resisting efforts at political persuasion? Are they more likely to demonstrate politically compatible points of orientation? These questions are addressed in the context of a study conducted during the course of the 1996 election campaign. In order to measure the accessibility of respondents’ partisan and ideological self-identifications, we record response latencies-the time re quired for respondents to answer particular questions. Based on our analysis, we argue that attitudes and self identifications are useful heuristic devices that allow individuals to make sense out of the complexity and chaos of politics. But some citizens are better able than others to employ these devices, and by demonstrating who these citizens are, the concept of accessibility becomes an important element in the explanation of political capacity.

Research Question

What is the key to the political capacity of citizens?

Are ideological and partisan orientations only important for those individuals who are able to distinguish themselves as strong partisans or strong ideologues, at the extreme points of the respective scales?

Is the utility of partisan and ideological reasoning contingent on the accessibility of an individual;s own self-identifications? Are people with accessible points of orientation more likely to invoke partisanship and ideology in formulating political judgments and resisting efforts at political persuasion? Are they more likely to demonstrate politically compatible points of orientation?

Does everyone possess a library of heuristic devices to use in uncertain circumstances? Under what circumstances is such a device likely to be most useful?

How might an individual confront government support for the arts absent such an ideological orientation?

Hypothesis:

Our argument is that the political relevance and heuristic utility of an attitude or an identification is directly related to its accessibility in the memory of an individual.

Such ideological orientations become more useful if they readily come to mind when an individual confronts a situation requiring a political decision or judgment.

Background:

The explicit or implicit lesson has been that strong ideologues and strong partisans are better able to exercise the duties of citizenship because they are better able to invoke clear principles when tthey are confronted with complex political issues.

Converse:

1) many citizens do not think in ideological terms

2) many demonstrate a high level of temporal instability in their opinions

3) many hold inconsistent opinions on seemingly related issues.

Questions have shifted to asking what manner can incapable citizens are able to reach political decisions.

accessible opinions, identitifications, and orientations are distinguished by their position within long-term memory.

- they are accessible because they are readily and easily available within individual cognitive structures (or schemas), and hence they are readily retrieved.

Data/Methods

previous studies have measured accessibility through the latency of the answer.

how long did it take the individual to answer the question - tracked through mouse/click time.

- the latency is the measure of accessibility.

Data: 1996 election campaign

2 samples

sample one: n = 2174

and a one stage snowball sample of these main respondents’ discussants n = 1475

drawn from the indianapolis metro area

st louis metro area

25 min interview

timed using latent timer which recorded the elapsed time between answers to two sequenced questions.

Results:

Citizens who readily think about politics in partisan or ideological terms are better able to employ these points of orientation as useful heuristic devices in making sense out of the complexity and chaos of politics.

In contrast to a model of online processing, our analysis builds on the idea that some citizens are unable to provide affective responses to opinion objects, while others-citizens with accessible heuristics-are able to for mulate responses on the spot using these heuristic devices

Lau, R. and D. Redlawsk. 1997. “Voting Correctly.” American Political Science Review. 91(3): 585-98.

Abstract:

The average voter falls far short of the prescriptions of classic democratic theory in terms of interest, knowledge, and participation in politics. We suggest a more realistic standard: Citizens fulfill their democratic duties if most of the time, they vote “correctly.” Relying on an operationalization of correct voting based on fully informed interests, we present experimental data showing that, most of the time, people do indeed manage to vote correctly. We also show that voters’ determinations of their correct vote choices can be predicted reasonably well with widely available survey data. We illustrate how this measure can be used to determine the proportion of the electorate voting correctly, which we calculate at about 75% for the five American presidential elections between 1972 and 1988. With a standard for correct vote decisions, political science can turn to exploring the factors that make it more likely that people will vote correctly.

Zaller, J. and s. Feldman. 1992. “A Simple Model of the Survey Response: Answering Questions versus Revealing Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science. 36: 579-616.

Abstract:

Opinion research is beset by two major types of “artifactual” variance: huge amounts of overtime response instability and the common tendency for seemingly trivial changes in questionnaire form to affect the expression of attitudes. We propose a simple model that converts this anomalous “error variance” into sources of substantive insight into the nature of public opinion. The model abandons the conventional but implausible notion that most people possess opinions at the level of specificity of typical survey items-and instead assumes that most people are internally conflicted over most political issues-and that most respond to survey questions on the basis of whatever ideas are at the top of their heads at the moment of answering. Numerous empirical regularities are shown to be consistent with these assumptions.

Bumper Sticker

Voters do not (for the most part) have preformed attitudes and make it up when confronted on a survey.

Research Question:

How sophisticated are voters?

Are they consistent?

Do surveys properly capture sophistication?

How do we develop a model that accommodates both response instability and response effects and that is crafted to the kinds of problems and data facing analysts of public opinion?

According to conventional attitude theory, individuals choose whichever prespecified option comes closest to their own position. But if, as we contend, people typically do not have fixed positions on issues, how do they make their choices?

Hypothesis/Argument:

Most citizens, we argue, simply do not possess preformed attitudes at the level of specificity demanded in surveys.

They carry around in their heads a mix of only partially consistent ideas and considerations.

- when questioned, they call to mind a sample of these ideas, including an oversample of ideas made salient by the questionnaire and the other recent events, and use them to choose among the options offered . But their choices do not, in most cases, reflect anything that can be described as true attitudes; rather, they reflect the thoughts that are most accessible in memory at the moment of response.

The heart of our argument is that for most people, most of the time, there is no need to reconcile or even to recognize their contradictory reactions to events and issues.

- each represents a a genuine feeling, capable of coexisting with opposing feelings and, depending on its salience in the person’s mind.

Context/previous research:

citizens don’t have very well informed attitudes. some debate of this. see Achen and Converse.

People are inconsistent in survey responses over time. Why?

Converse argues large portions of an electorate do not have meaningful beliefs even, even on issues that have formed the basis for intense political controversy among elites for substantial periods of time.

Achen disagrees a bit.

they are stable but there is error as a result of survey design/issues.

- mapping true attitudes to vague langue of survey questions is hard.

Achen assumes that all respondents have “true attitudes”

Question ordering influences all levels of respondent.

Surveys frame issues and make certain things salient.

Hochschild particularly emphasizes ambivalence in many of her respondents

this ambivalence is interesting.

- they are being probed for the opinion but the ambivalence shows the need for a discourse to reach a conclusion.

a schema is a cognitive structure that organizes prior information and experience around a central value or idea and that guides the interpretation of new information and experience

- this kind of sounds like a belief system or at least closely related.

Zaller’s model will follow the assumption of ambivalence in people’s political beliefs.

Axioms

The ambivalence axiom. Most people possess opposing considerations on most issues, that is, considerations that might lead them to decide the issue either way.

The response axiom. Individuals answer survey questions by averaging across the considerations that happen to be salient at the moment of response, where saliency is determined by the accessibility axiom.

The accessibility axiom. The accessibility of any given consideration depends on a stochastic sampling process, where considerations that have been recently through about are somewhat more likely to be sampled.

Deductions:

We should find that people are, in general, more politically involved have more considerations at the top of their heads and available for use in answering survey questions.

we would expect persons who have greater interest in an issue to have, all else equal, more thoughts about that issue readily accessible in memory than other persons.

- dont have good data for this but have some

We should find strong correlations between measures of people’s thoughts as they answer a survey item and the direction of decision on the item itself.

If as the model claims, individuals possess competing considerations on most issues, and if they answer on the basis of whatever ideas happen to be at the top of their minds at the moment of response, one would expect a fair amount of over-time instability in people’s attitude reports.

Citizens would have central tendencies that are stable over time, but their attitude statements would fluctuate greatly around these central tendencies.

Attitude reports formed from an average of many considerations will be more reliable indicator of the underlying population of considerations than an average based on just on one or two considerations

People should be more stable in their responses to close-ended policy items conserning doorstep issues-that is, issues so close to everyday concerns that most people routinely give some thought to them.

Greater ambivalence ought to be associated with higher levels of response instability.

If, as the model claims, people are normally ambivalent on issues but answer on the basis of whatever ideas are most accessible at the moment of answering, raising new considerations in immediate proximity to a question should be able to affect the answers given by making different considerations salient.

Most ambivalent - are the people that should be most strongly affected by artificial changes in question order.

The tendency of people to base attitude reports on the ideas that are most immediately salient to them, as specified in Axioms 2 and 3, well explains such effects.

race of interviewer effects

reference group effects

priming effects of television news

framing effects of question wording and question order

Having had their ideological orientations made salient to them just prior to answering policy items, those respondents who possess such orientations are more likely to rely on them as a considerations in formulating responses to subsequent policy questions, thereby making those responses more strongly correlated with their ideological positions and hence also more ideologically consistent with one another.

We therefor expected that responses following the stop-and-think treatment would be, all else equal, more reliable indicators of the set of underlying considerations than responses made in the standard way, that is, in the retrospective condition.

- struggle to confirm this one.

Results/Findings:

- The conflicts most responsible for response instability is conflict that occurs across rather than within interviews and that respondents are often unaware of their conflict as they answer questions.

Other:

mention of the “on-line” model/ people use a judgment operator to update continuously their attitudes “on-line” as they acquire new information.

People are said to store their updated attitudes in long-term memory and retrieve them as required, rather than, as in our model, create attitude statements on the spot as they confront each new survey question.

- They are still skeptical about this because citizens must answer such a large variance of questions on survey for the on-line processing of all relevant information.

Week 5: Tolerance and Trust

Lecture Notes:

Research Designs

Questions: What is the goal?

puzzles

description

causal

Formal theory is good for hypothesis generation.

hypothesis generation -> hypothesis testing

testing:

observational

experimental

causal

control and treatment are the same!

groups are the same on controllable and uncontrollable. important.

control confounds:

randomization

- internal validity

manipulation

internal validity is confidence in the study between x and y.

external validity = generalizablility?

- does this study accurately represent the population.

Writing a proposal - need to justify why it exist.

- claim?

Trust/tolerance stuff:

measurement

most disliked group.

- are you willing to let that group speak? etc.

we should give more groups.

measure how much you like/dont like that group.

also measure your support for civil liberties.